The Parable of the Prinia’s Egg: An Allegory for AI Science

When European scientists first encountered the eggs of the tawny-flanked prinia Prinia subflava, an African nesting bird, they believed they understood what they had found. The prinia lay eggs that exhibited swirls, speckles, and coloration unique to each individual bird. What purpose do such patterns serve in nature? Surely, scientists agreed, these markings allowed the eggs to camouflage and blend into the nest.

One 19th century naturalist, Charles Francis Massey Swynnerton, offered an alternative explanation. Why would each bird have its own unique patterns? Swynnerton believed that the markings functioned as watermarks, allowing the nesting bird to differentiate its own eggs from those of the cuckoo finch Anomalospiza imberbis. The cuckoo finch is an obligate brood parasite, meaning that it does not build its own nest, but instead lays its eggs in the nests of other birds, particularly the prinia.

Since its proposal, evidence for Swynnerton’s hypothesis has accumulated. The camouflage hypothesis was based on anecdotal observations of eggs, without correlational or experimental data. In contrast, evidence for the brood parasite hypothesis comes in diverse forms, using many different frameworks for reasoning about causality and explanation, adding up to an indisputable scientific arsenal. What can AI researchers learn from the mature science of biology to strengthen our own evidence and reliably interpret how neural network traits contribute to model behavior?

Instance level interpretability

Most interpretability work, and much work in science of deep learning, relies on passive observations of phenomena with post-hoc explanations for how artifacts in the model contribute to model outputs. Like the early ornithologists suggesting that prinia eggs were camouflaged, interpretability researchers often identify some phenomenon and link it to model decisions based solely on their intuitions. Some work attempts a more principled approach, by intervening on the trained model to demonstrate that a given feature or circuit has a predictable effect on model judgment. Both approaches might be classed as instance-level, as they consider the behavior of a fully trained model on a given input sample.

In the past, I have called this reliance on fully trained models Interpretability Creationism, and suggested that interpretability researchers instead measure the indicators they focus on throughout training. However, I have not detailed how these creationist approaches can lead us astray, nor have I proposed a clear framework for understanding development. Such a framework falls under the philosophical field of epistemology, the study of what makes a belief justified.

Syntactic Attention Structure

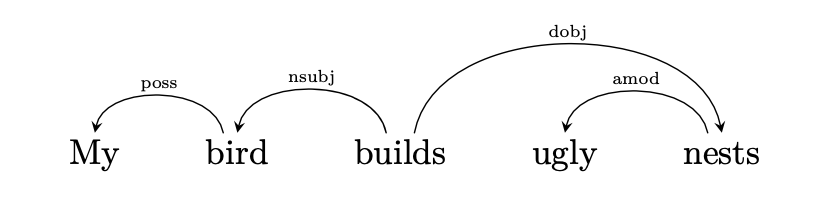

To address the epistemology of interpretability, let us construct a case study of the scientific literature on an observed phenomenon in neural networks. One well-documented and intuitive behavior is how Transformer-based masked language models (MLMs) have specialized attention heads that focus on a specific dependency relation, a trait we will call Syntactic Attention Structure (SAS). We can illustrate SAS with an example sentence.

In the preceding sentence, the model might be called upon to predict the masked-out target word builds. During inference, its specialized nsubj head will place its highest weight on bird, while its specialized dobj head will place its highest weight on nests. This specialization behavior emerges naturally, without any explicit inductive bias, over the normal course of training for models like BERT.

SAS was discovered concurrently in two papers. First, Clark et al. (2019) observed that specialized attention heads provide an implicit parse, which aligns with prior notions of dependency syntax, as measured by Unlabeled Attachment Score (UAS). This observation provides instance-level observational evidence for the role of SAS in masked language modeling. Second, Voita et al. (2019) discovered that pruning specialized syntactic heads damaged model performance more than pruning other heads, providing instance-level causal evidence for the role of SAS. What’s missing from these studies, from an epistemological standpoint?

When does instance-level analysis fail?

There is an assumption underlying claims in interpretability: that the observed phenomenon measured by the interpretable indicator metric, such as implicit parse UAS, plays a role in determining some target metric, such as MLM validation loss or grammatical capabilities. However, instance-level evidence like the prior work on SAS might not support this assumption.

First, instance-level observational evidence might highlight artifacts that arose as a side effect of training, rather than as a crucial element in model decisions. That is, the poorly-understood dynamics of training might lead to structures emerging that are not required at test time. In evolutionary biology, such artifacts are called spandrels; proposed examples include human chins and musicality.

Second, instance-level causal evidence may be stronger, but remains flawed as evidence for the effect of SAS. For example, what if SAS emerges early in training, and gradually the model develops a more complex representation that does not rely on SAS, but the specialized heads have already become entangled with the rest of the high dimensional representation space? Then these specialized heads are vestigial, like a human tailbone, but are integrated into distributed subnetworks that generate and cancel noise, so the network may be particularly brittle to their removal. Another weakness of instance-level causal interpretation is that it may claim that a given behavior is unimportant, when in fact the model relied on that trait to converge on its final solution, as webbing evolves for gliding before an organism can develop wings.

Epistemology and evidence

As we see in the example of SAS, treating a model atemporally, in a manner detached from its development, might yield intriguing phenomena and even suggest insights. However, in order to strengthen the evidence for these insights, we argue for applying developmental analysis. Developmental history may shed more light on the effect of a given indicator on a target metric, compared to atemporal data.

Beyond the question of whether we have access to development data, there are three widely used categories of evidence in the scientific literature. Any one of the following categories might apply in either atemporal or developmental settings.

- Observational: For example, BERT exhibits SAS and also demonstrates grammatical capabilities. This is evidence based on passive observation of a given phenomenon. Atemporal observations are not strong evidence of a relationship between that phenomenon and the target of analysis, like a generalization metric. However, observations of development may support a relationship between the indicator and target metrics.

- Correlational: For example, SAS is correlated with grammatical capabilities across a population of multiple models. This is evidence based on natural variation of a given phenomenon.

- Causal: For example, grammatical capabilities are affected by intervening on SAS. This is evidence based on experimental interventions on the indicator phenomenon.

Cracking the case of the cuckoo culprit

Returning to the example of the prinia, the assumption that their egg markings served as camouflage was based on atemporal observational evidence. Brood parasites (the indicator) do, in fact, drive the evolution of egg markings (the target of analysis). There are several epistemically strong pieces of evidence that ornithologists have found for that influence, including:

- Atemporal correlational: A brood parasite’s favored hosts, like the prinia, have more individualized markings than other nesting birds.

- Developmental observational: On continents with a longer evolutionary history of brood parasitism, such as Africa and Australia, nesting birds have more elaborate egg patterns compared to Europe, which has a shorter history of parasitism, or North America, which has no obligate brood parasites at all. If we treat each continent as though we are observing a checkpoint at some point in the evolutionary arms race between parasite and host, we can see that egg markings appear to be dependent on brood parasitism during evolutionary development.

- Developmental causal: Invasive species of nesting birds provide a natural experiment for testing the link between brood parasitism and egg markings. When a host species spreads from its native range to an island without brood parasites, Australian ornithologists have observed that the species gradually loses its intricate egg markings over subsequent generations.

What’s the evidence for Syntactic Attention Structure?

Does SAS play a significant role in the capabilities of a masked language model? In our latest paper, Sudden Drops in the Loss: Syntax Acquisition, Phase Transitions, and Simplicity Bias in MLMs, we test the impact of SAS by mirroring the variety of evidence collected by ornithologists. Let’s walk through the relevant results.

Atemporal correlational

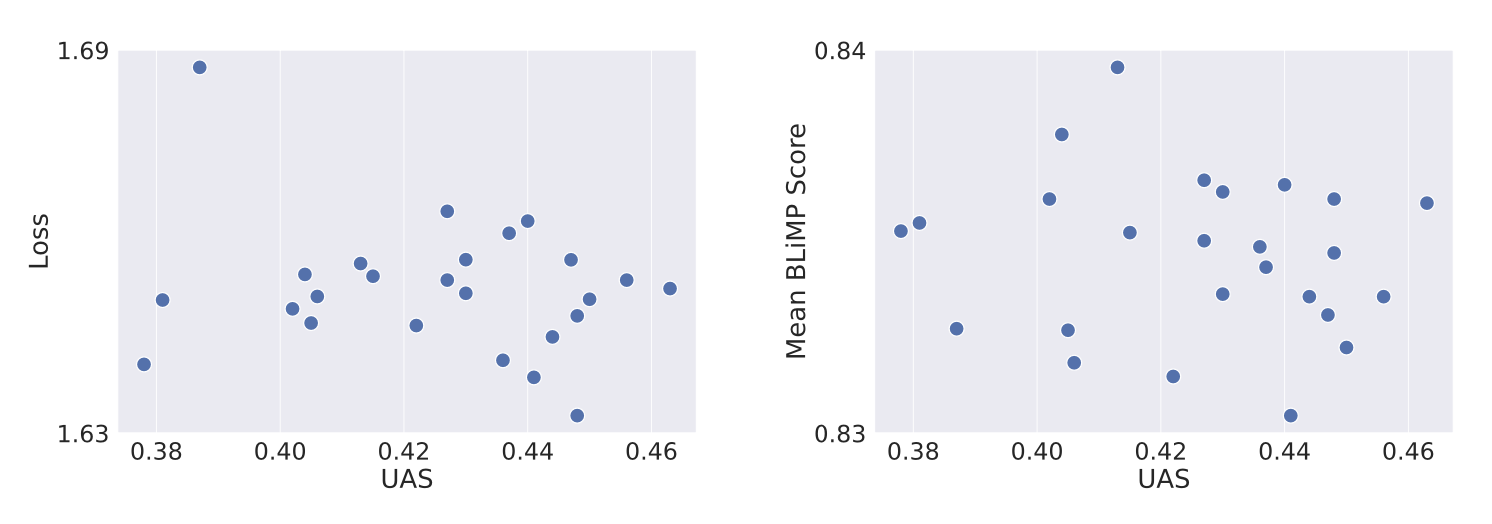

Correlational evidence is stronger when the variation in a population is known to be random, other than the metrics in focus, because this scenario allows us to control for the effect of confounding factors. This is the reason why, for example, genetics studies that use adopted children are stronger than those that study children raised by their biological parents, thereby confounding nature and nurture. Fortunately, deep learning allows us to generate random variation across models easily, by varying the training seed.

Unfortunately, the correlational results above seem to be bleak for the idea that SAS is crucial to model capabilities. Using 25 independently trained MLMs from MultiBERTs, we see no significant correlation, or even a clear pattern, between UAS (our SAS metric) and either validation loss or linguistic capabilities (in the form of BLiMP score).

Should we abandon SAS as a phenomenon unrelated to performance in practice? Not so fast. It may be that random variation does not elicit strong enough differences in SAS to register a behavioral difference. In order to dig deeper, we now turn to using a developmental lens by considering the training process.

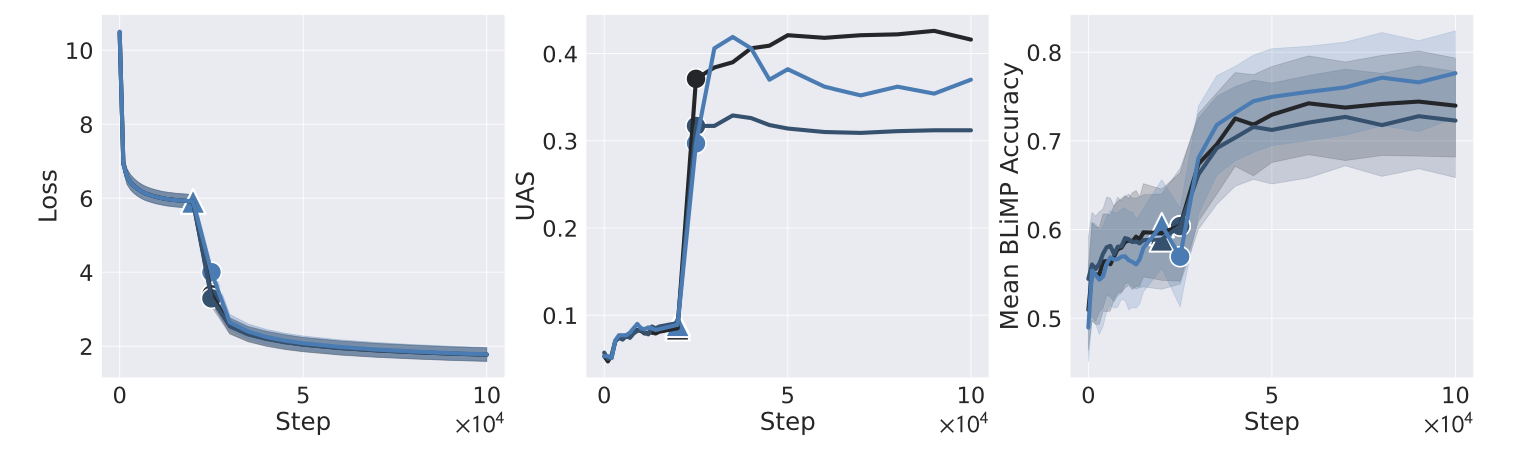

Developmental observational

Next, we passively observe SAS in an MLM model (a retrained BERT_base run with 3 different random seeds), but consider it during the entire course of training rather than at a single checkpoint. Results here appear to be far more promising, thanks to the clarity of an abrupt breakthrough in UAS about 20K steps into training. First, we see that there is a precipitous drop in loss coinciding with this UAS spike (marked ▲). Then, after UAS reaches its peak and begins to plateau, we observe an immediate jump in the MLM’s particular linguistic capabilities, as measured by BLiMP (marked ⏺). It certainly appears that the former is dependent on the latter. While we can directly observe that internal SAS structure precedes the acquisition of linguistic capabilities, though, can we guarantee that SAS precipitates linguistic capabilities?

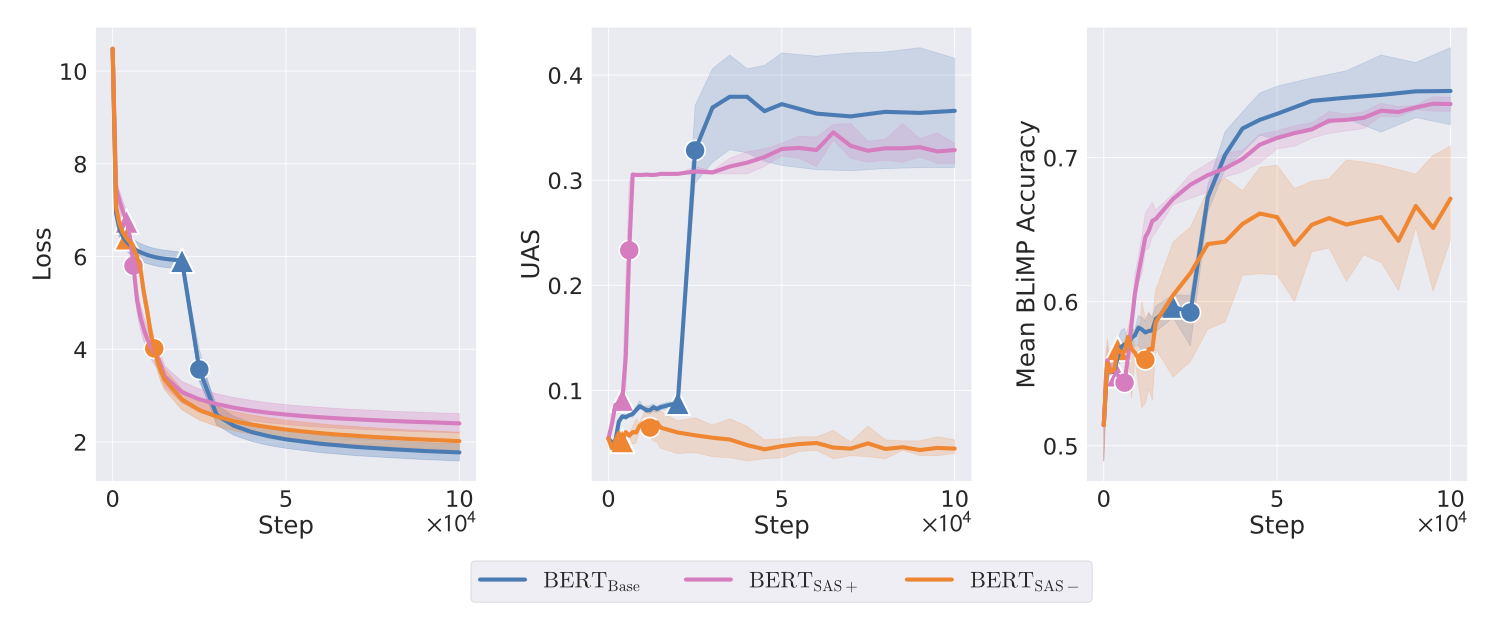

Developmental causal

To study how connected these consecutive phase transitions are, we intervene on the training process to suppress and promote SAS, yielding models respectively called BERT_SAS- and BERT_SAS+. Although neither promoting nor suppressing helps long term MLM performance, observing the training process shows clear evidence of a dependency. Promoting SAS leads to an earlier UAS spike, which indeed precipitates an earlier spike in linguistic capabilities. Meanwhile, suppressing SAS prevents any UAS spike and leads to persistently poor linguistic capabilities throughout training.

Conclusion

By monitoring MLM training, we have found epistemically strong evidence of a connection between SAS and model performance, in particular through linguistic capabilities. These results are described in a new paper led by Angelica Chen working with Ravid Schwartz-Ziv, Kyunghyun Cho, Matthew Leavitt, and me: Sudden Drops in the Loss: Syntax Acquisition, Phase Transitions, and Simplicity Bias in MLMs.

Beyond the results obtained through our approach to interpretability epistemology, this paper also presents a large number of related findings. The full paper is worth reading, I think, as the results described here might not even be the most interesting part! We link these interpretable training dynamics to the broader literature on simplicity bias, model complexity, and phase transitions. We even show how our methods can be used to improve MLM performance by suppressing SAS briefly at the beginning of training. By questioning a seemingly settled result in interpretability, we developed a deeper understanding of MLM training.

All preceding discussion of the research on brood parasites comes from one of my favorite books, Cuckoo: Cheating by Nature by Nick Davies. I highly recommend it to anyone interested in a deep dive on the evolution of a single survival strategy.